Feeding the Elite, Poisoning the People: The Dark Reality of Food in China

In the Matrix franchise, reality is an illusion delicately constructed by those in power. This circumstance mirrors the situation in contemporary China, where some of the best-tasting milk is found, not because of its quality, but due to the abundance of preservatives, flavor enhancers, and other chemicals measured out with precision just to cut corners and reduce production costs. There are still concerns about adulteration, excessive antibiotics, and distrust in Chinese dairy today. This issue pertains not only to milk but encapsulates a majority if not all food products. A brief article published by the state-owned news network Xinhua states that the Chinese government has put out new regulatory measures to improve food safety standards in China. These improved measures include enhanced inspection and quarantine certification for meat, transportation of liquid foods, and campus food safety management.[1] However, these regulations would not solve the issue, as the issue is simply a microcosm of a much bigger issue within Chinese society. Additionally, Xinhua has a history of cherry-picking information to make public to not place the Chinese government in a bad light. Subsequently, many argue that food safety issues such as scandals, regulatory failures, and other food safety issues are not unique to China. This is a commonly used propaganda talking point utilized by the Chinese government. This form of whataboutism creates a false sense of security by diverting attention while simultaneously not addressing the core issue. Ultimately, these half-measures and deflections are simply a calculated attempt to shape perception and preserve political legitimacy. The food safety crisis in China needs to be resolved, as it is not merely a public health issue but a manifestation of institutional inequality, driven by a culture of scarcity, distrust, and opportunism, upheld by systems that protect the elite while exposing ordinary citizens to adulterated products such as melamine-laced infant formula and gutter oil, and intensified by a government more invested in control and scapegoating than in genuine reform.

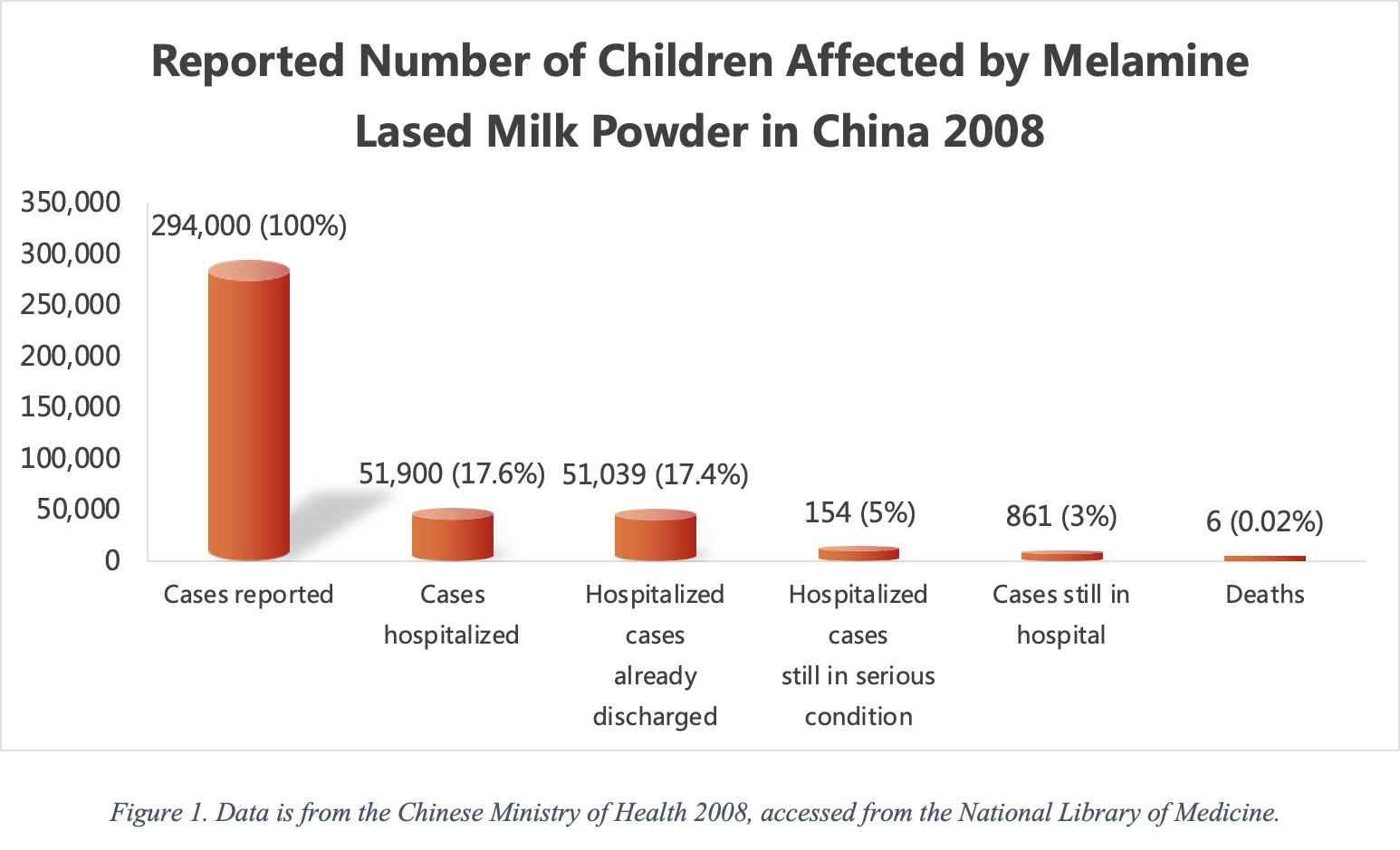

One of the most notorious examples of this ongoing food safety epidemic is the Chinese 2008 milk powder scandal, in which infant formula was found to be adulterated with melamine, leading to widespread illness and public outrage. The addition of melamine artificially inflates the nitrogen content of the product, which, in turn, provides a higher reading of protein content without actually increasing its nutritional value.[2][3] According to the Ministry of Health of China, 294,000 children suffered negative effects from tainted infant formula, 51,900 were hospitalized, all except 861 of which were discharged, and the death of six infants was officially reported, as demonstrated in Figure 1. It should be noted that official statistics released by the Chinese government are often inaccurate, as the lack of transparency combined with efforts to avoid public backlash results in data that hides the true severity of such incidents. As a result, official statistics fail to highlight the inevitable lifelong kidney issues, the resulting deaths months after the scandal, or the permanent disfigurement suffered by the victims.[2][3][4] This incident acts as a microcosm of the reality of the food safety issue in China, as quality inspection is often perfunctory, and shortcuts are taken wherever possible in order to maximize profits and lower costs, even if it comes at the expense of public health.

Though the infamous milk powder scandal took place in 2008, the quality of milk in China is still a serious concern. Contemporary manufacturing environments reflect the conditions portrayed in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. The article "Ten Days in Inner Mongolia: An Internship Journal at Mengniu’s Ice Cream Subcontracting Facility" offers a firsthand account of the unhygienic and inhuman conditions of the second tier of production in the Chinese milk industry. Underpaid workers live in cramped onsite dorms, with garbage being burned right outside the factory floor. The factory is filled with the combined smell of smoke, burnt plastic, sugar, and dairy manifesting as a thick fog. Products or ingredients that are dropped on the floor would be picked up and placed back into the production line or the pile of finished products. The yogurt ice cream produced does not contain any yogurt, the chocolate cones do not contain chocolate, and the place of these ingredients is filled by cheap artificial substitutes.[5][6] The factory’s own inspection process finds that ten percent of the finished product is contaminated in nearly every check, but the defective products are sold regardless.[6] This internship journal exposing this was taken down within two hours and is still heavily censored in China, as is often the case for whistleblower accounts that threaten corporate or governmental reputations.[5][6] Dairy production in China often falls below international standards. Unlike in countries where Holstein Friesian cows have been selectively bred over centuries to maximize milk yield, many Chinese farmers have not maintained consistent genetic improvement and breeding practices.[5] As a result, the quality of the breed has declined, leading to genetic defects, reduced productivity, and a lower quality yield.[7] The dairy cows are often fed with low-quality or recycled water, and suboptimal food. This, combined with the extensive use of antibiotics inevitably plummets the quality of the product. Said quality is later substituted with chemicals such as melamine to increase nutrition content, antibiotics to suppress bacterial contamination, and artificial flavors to mask the suboptimal taste.[8] The extensive utilization of chemicals results in milk produced in China being arguably superior taste-wise, as the substance no longer bears any substantial resemblance to actual milk.

Similar to the abhorrent conditions of dairy products, the use of gutter oil also sparked public outcry a number of years ago. The restaurant industry saw a massive rise in China following the economic growth of the early 2000s, which caused the urban population to grow rapidly. This resulted in many restaurants partaking in unsanitary practices such as the use of gutter oil in order to save costs and meet market demands. Gutter oil refers to the use of illicit cooking oil in China, often waste oil collected from restaurant fryers, drains, or street gutters.[9] The use of gutter oil is most prominent amongst restaurant workers and oil producers, where oil naturally floats to the top amongst waste and is collected and refined to save costs on cooking oil. The reselling and reuse of oil from unsanitary sources poses serious health risks, including exposure to carcinogens and harmful bacteria.[9] Gutter oil is simply a manifestation of a much bigger issue within Chinese society.

The prevalence of such profit-driven unethical practices, such as gutter oil, reflects misgovernance by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). For instance, in high-trust societies such as Denmark, the United States, and Japan, public assistance and community support such as food pantries, clothing drives, and communal kitchens exist for those in genuine need. Social norms discourage the abuse of these resources, as the people within these societies generally refrain from exploiting such systems. However, similar systems cannot exist in contemporary China, as events such as the Great Chinese Famine and the Cultural Revolution have resulted in a uniquely mainland Chinese mindset of scarcity, distrust, and opportunism.[10] These historical traumas brought upon by the communist government have resulted in a self-orientated mentality where environmental preservation, ethical considerations, and collective welfare are largely overlooked in both business and daily life. Basically, anything that can be exploited will be exploited, especially if it is free. For example, most parts of China will not have free toilet paper in bathrooms because people would treat it like a giveaway rather than a shared utility.[10] Similarly, a lot of newly arrived Chinese students collect goods meant for the homeless, despite being financially secure, highlighting a troubling disregard for social norms, ethics, and the intended purpose of welfare systems. This, combined with the government’s laissez-faire attitude towards public health, is the underlying reason for melamine in milk powder and the use of gutter oil. Public attention surrounding such scandals is often a whisper in the winds of time. As outrage inevitably dies down with time, the people of China continue to consume gutter oil, either knowingly or unknowingly.

More concerningly, another main cause of the food safety epidemic stems from the phenomenon of special food for the elite, known as the "tegong" or special supply system in China. It is a practice that stemmed from the early Communist era, with premium food produced, procured, inspected, and allocated based on rank. According to Tsai, from the Institute of Political Science at Academia Sinica, “The tegong system was adopted from the Soviet Union, which from its inception provided its government officials with daily necessities according to their respective grades. The higher the position, the better the benefits received.” The earliest iterations of the system did not emphasize the quality of the food since food was limited. However, after the establishment of the People’s Republic, officials from the Soviet Union were sent to help the CCP establish its own special food supply system.[11] This system proved useful to the leadership during the Great Chinese Famine, as it ensured that high-ranking officials had a sufficient food supply that was even able to provide off-season fruits, while millions of ordinary citizens suffered from starvation.[12] In modern times, this system has evolved from providing food during a time of undernourishment to now ensuring leaders have food that is of a higher safety standard. Safe from extensive pesticides, chemical fertilizers, and harmful additives used in mass food processing, this insulates their food supply from ordinary people, and as a result, removes the need to resolve the abhorrent food safety standards that they are kept safe from. The existence of systems such as tegong highlights the institutionalized inequality in contemporary China; food safety is simply a symptom of a much larger issue. If the same enthusiasm and resources used to ensure the elite have safe food could be used to resolve the greater issue for the rest of the nation, there would be no doubt that the food safety issue could face a resolution.

This same dynamic can be seen in how the CCP approaches other public health and environmental crises. The CCP has the capacity to resolve food safety issues but lacks the incentive to do so since “the people that matter” are not directly affected. A contrast can be seen in cases such as the government’s “War Against Pollution,” in which air pollution became a priority only when it began affecting the health of the elite and receiving international attention.[13] Severe smog in Beijing led to public outcry and even "hazard pay" for international employees assigned to the country.[14] In response, the government relocated coal plants away from the capital and even banned the use of firepits during the winter for cities around the capital.[15][16] This resulted in noticeable improvements in air quality for the capital while shifting environmental burdens onto surrounding rural regions.[17] This further exemplifies the way the general public suffers the consequences of improving the health of elite individuals. The sudden ban on firepits in underdeveloped areas, often the primary source of heating, left many without adequate heating during harsh winters. However, despite these abrasive measures, food safety has not seen the same urgency because, in contrast to air quality, the privileged class does not consume the same food. Spending large amounts of time and money on an issue that would not have significant visible effects useful to propaganda is not in the self-oriented and shortsighted mindset of the Chinese government, leaving the general population to suffer from unsafe food standards.

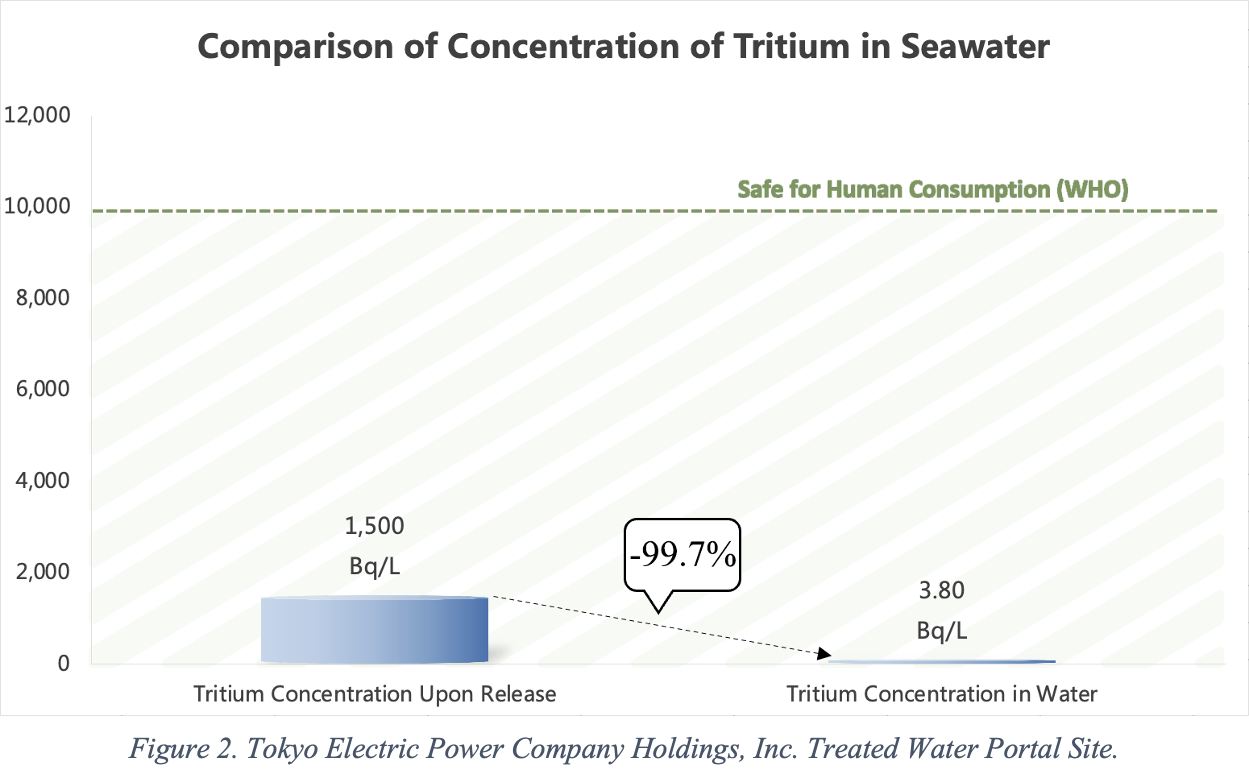

The Chinese government not only fails to regulate food standards but simultaneously utilizes the issue in domestic propaganda. This is evident in the discharge of radioactive water of the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant beginning in 2023, where the Chinese Government especially had been promoting the idea that Japan is destroying the environment to its populous. As a result, the Chinese populace started irrationally stockpiling salt and avoiding seafood in fear of the harmful effects of nuclear waste.[18][19] This reaction could be seen as completely irrational; WHO guidelines dictate that water containing under 10,000 Bq/L of tritium is safe for human consumption. The discharge of treated radioactive water from Japan has been extensively filtered and tritium concentrations upon release would be 1,500 Bq/L. The sheer amount of water in the ocean would dilute the discharged tritium to levels far below any health risk, as the seawater surrounding Fukushima Prefecture after the release contains less than 3.8-4.2 Bq/L, as visualized in Figure 2. This, combined with the fact that only 7,800㎥ of this water would be released each month over the span of many years, renders the impact negligible on both the environment and human health.[20] Meanwhile, nuclear power plants in China have been releasing water containing higher amounts of tritium into the ocean for many years without strict scrutiny under international organizations.[21] Long-term health effects from the negligible amounts of tritium in the ocean as a result of Japan’s discharge would be both figuratively and literally a drop in the ocean in comparison to the consumption of unsafe food such as melamine-laced milk, gutter oil, and long-term exposure to visibly polluted air. The narrative placed out by the Chinese government through news outlets such as Xinhua does not directly address pre-existing food safety issues, while it simultaneously diverts public attention away from domestic failures and shifts the blame onto an external enemy. This discrepancy highlights how environmental issues are not only inconsistently addressed but also exploited for political narratives, often at the expense of public understanding and scientific accuracy.

Despite the realities of daily life in the People’s Republic, upon hearing any criticism of the so-called “glorious government,” such as pointing out failures when it comes to food safety, a vast majority of the population will instinctively deflect, deny, or even defend the very system that neglects their well-being. Thus, many argue that food safety issues are not unique to China to cope with the realities of living in a system that tells the slaves that they are the masters. The government’s tactic of pointing the blame onto foreign strawman enemies distracts the people from internal systematic failures. This propaganda talking point is commonly used by the Chinese government. As it discourages emigration to maintain stability, since the bottlenecked information combined with brainwashing pushes the narrative that tells the people that there is nothing to envy from the outside world. The same ideas stifle the pursuit of the right to place pressure on the government and the right to free speech, the lack of which is the exact environment that enables the existence of food safety issues in an oppressive system. The knee-jerk reaction of deflection and denial is often not out of genuine trust in the system, as word and recorded videos of food manufacturing and tragedies do proliferate on the Chinese internet, but the systemic government propaganda combined with a lack of access to alternative perspectives effectively distorts public perception and reinforces a manufactured sense of nationalistic loyalty.

It is imperative that the issue of food safety in China be addressed because of the extensive consequences on public health and lifespan for everyone other than the beneficiaries of the system; the repercussions of this issue are a result of the mindset of scarcity, distrust, and opportunism combined with the mechanisms in place that insulate the “people that matter,” which leads to the addition of melamine in infant formula, use of gutter oil, and the weaponization of information to deflect blame onto a strawman enemy. The best-tasting milk in the world is simply a byproduct of corporate greed, gutter oil is a manifestation of a low-trust society, the tegong system removes any incentives for change, and the issue of food safety is simultaneously used to fuel the propaganda that made all this possible, or even accepted. As Morpheus from the Matrix franchise puts it "Most of these people are not ready to be unplugged. And many of them are so inured, so hopelessly dependent on the system, that they will fight to protect it."

[1] "China Unveils New Food Safety Regulatory Framework Across Full Supply Chain"

Xinhua, 19 Mar. 2025

https://english.news.cn/20250319/55f66693990a44f0ae6a65ac15105c06/c.html[2] “Chinese Figures Show Fivefold Rise in Babies Sick From Contaminated Milk”

The Guardian, 2 Dec. 2008

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2008/dec/02/china[3] “The Melamine Incident: Implications for International Food and Feed Safety”

Environmental Health Perspectives vol. 117,12 (2009): 1803-8

doi:10.1289/ehp.0900949[4] "The China Melamine Milk Scandal and Its Implications for Food Safety Regulation"

Food Policy, vol. 36, no. 3, 2011, pp. 412–420. ScienceDirect

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodpol.2011.03.008[5] “Chinese Dairy Giant Accused of Selling Spoiled Ice Cream”

France 24, 20 June 2012

https://observers.france24.com/en/20120620-chinese-dairy-giant-accused-selling-spoiled-ice-cream-mengniu-milk-scandal-student-internship-internet-censored[6] “Mengniu Ice Cream Scandal: Postings Deleted, Informant Silenced”

[7] “Prevalence of Nine Genetic Defects in Chinese Holstein Cattle”

Veterinary Medicine and Science, vol. 7, no. 5, Sept. 2021, pp. 1728–1735

doi:10.1002/vms3.525[8] "Mengniu, Yili, and the Dark History of China's Dairy Industry"

China Digital Times, 13 July 2020

https://chinadigitaltimes.net/chinese/649986.html[9] “China Food Safety Hits the ‘Gutter’”

Food Control, vol. 41, 2014, pp. 134-138

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2014.01.019[10] “The Great Uncivilization of America Is Here”

Medium, 4 Jan. 2025

https://medium.com/@ossiana.tepfenhart/the-great-uncivilization-of-america-is-here-e569d5aca5e7[11] "Delicacies for a Privileged Class in a Risk Society: The Chinese Communist Party's Special Supplies Food System"

Issues and Studies, vol. 52, no. 2, 2016, pp. 1-29

https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/delicacies-privileged-class-risk-society-chinese/docview/1886609450/se-2[12] “China's great famine: 40 years later”

BMJ (Clinical research ed.) vol. 319,7225 (1999): 1619-21

doi:10.1136/bmj.319.7225.1619[13] “China’s War Against Pollution Extraordinarily Successful: University of Chicago Researcher”

Air Quality Life Index, 25 Mar. 2022

https://aqli.epic.uchicago.edu/news/chinas-war-against-pollution-extraordinarily-successful-university-of-chicago-researcher/[14] “Paying for Pollution: Air Quality and Executive Compensation”

Pacific-Basin Finance Journal, vol. 74, 2022, 101823

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pacfin.2022.101823[15] "300 Firms Leaving Beijing to Reduce Smog in Capital"

China Daily, 19 May 2014

https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/regional/2014-05/19/content_17525820.htm[16] "Polluting Firms Face Tougher Rules in Beijing"

Shanghai Daily, 27 July 2014

http://www.china.org.cn/environment/2014-07/27/content_33068353.htm[17] "Theorizing Socio-Environmental Reproduction in China’s Countryside and Beyond"

Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, vol. 4, no. 4, 2020, pp. 1687–1702

https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848620970125[18] "Fukushima Wastewater Prompts a Battle Over Fish"

The New York Times, 25 Aug. 2023

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/25/world/asia/fukushima-water-seafood-japan-china.html[19] "China’s Biggest Salt Maker Urges Public Not to Panic Buy After Fukushima Discharge"

Voice of America, 25 Aug. 2023

https://www.voanews.com/a/china-s-biggest-salt-maker-urges-public-not-to-panic-buy-after-fukushima-discharge-/7240669.html[20] "Discharge History"

Tokyo Electric Power Company Holdings, Inc.

https://www.tepco.co.jp/en/decommission/progress/watertreatment/performance_of_discharges/index-e.html[21] "Fukushima: China Accused of Hypocrisy over Its Own Release of Wastewater from Nuclear Plants"

The Guardian, 25 Aug. 2023

www.theguardian.com/environment/2023/aug/25/fukushima-daiichi-nuclear-power-plant-china-wastewater-release-

Senkaku Dispute: Sino-Japanese Relations

The Dispute Over Rocks ... -

Seeking Truth from Facts: Bias in Tragedy

California wildfires and China ... -

.png)

北京高中一学生被同学用剪刀连刺太阳穴

教委学校冷漠回应家长实名曝光